From cleaning to machining, engine builders are leaving the hands-on approach behind in favor of more automated methods that are also more friendly to the environment. If you’re looking for a system that works as good as some of your methods, ultrasonic cleaning might be a good choice for your shop.

Just as the Von Trapp family’s hills were alive with the sound of music, engine shops have become more familiar – and profitable – with the sound of ultrasonic cleaning. Many shops are sounding out the ways to add one of these cleaning wonders that have been around in other industries for years, but are now more affordable for smaller shops.

Related Articles

Most new employees start in the cleaning department. If they can’t hack it there, then there’s no chance of letting an inexperienced hand do any machining, that’s for sure. While cleaning may be considered a lowly job, it is actually one of the most important. Shops typically employ several cleaning methods in their rebuilding procedures – including having the new guy do manual labor – because the parts must be “good as new” when they are put back into service and sent out the door to a customer. It’s probably fair to add that cleaning is one of the most time-consuming processes of any engine building operation as well.

While old methods and unskilled manual labor still work to get parts clean, many shops don’t have the extra hands to do the work (more on that topic on pg. 38). There are also more regulations that have cracked down on the use of harsh chemicals and how you dispose of waste. So, what is an engine builder to do when faced with all these obstacles? Automate as much as possible.

From cleaning to machining, engine builders are leaving the hands-on approach behind in favor of more automated methods that are also more friendly to the environment. If you’re looking for a system that works as good as some of your methods, ultrasonic cleaning might be a good choice for your shop.

In a recent Machine Shop Market Profile study conducted by Engine Builder magazine, respondents said they spend 22 percent of their production time disassembling and cleaning engine parts. And this trend is on the rise from 14 percent five years ago.

One engine builder said his shop spends about four hours per engine in cleaning alone. If you multiply that by the total number of engines built per month (24 on average), that’s 96 hours a month you spend cleaning! Ultrasonic cleaning systems help reduce the hands-on labor time involved, but it’s not 100 percent automated yet as there’s still some manual cleaning that needs to be performed.

But before you run out to buy the least expensive machine you can find on the internet you should do your homework first, because not all machines are the same. Ultrasonic machines come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes and have been commonly used in the jewelry industry for years. Jewelers often use a small tabletop machine to clean rings, necklaces and bracelets that are made of different types of metals. These machines operate at a frequency that works for that industry, but it is not necessarily the best choice when it comes to cleaning engine parts.

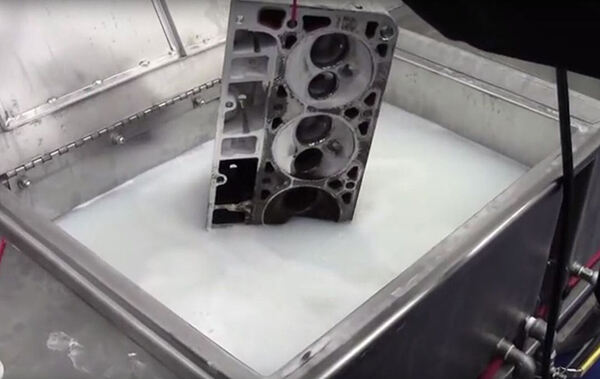

An ultrasonic cleaner may resemble a hot tank, but the secret is in the cavitation it produces (bubbles that form and collapse) in the cleaning solution.

“The ultrasonic waves create implosion cavitations on the surface of the part,” says Andy Logan, senior chemist for the ArmaKleen Company. “These implosions disrupt the integrity of the soil to be removed.”

Ultrasonic systems use a transducer to convert electrical energy into sound waves, which in turn, creates cavitation bubbles that scrub the parts. The bubbles form and collapse rapidly along the surface and also penetrates small crevices and galleys. As the bubbles implode, they pull dirt and particles away from the surface and up to the top of the solution.

“Variable transducers allow for the tuning of the sound waves,” Logan explains. “But variable tuning brings risks of parts damage. The lower the frequency, the more penetrating the sound waves are to the substrates. Lower frequencies can damage even steel.”

Using a low frequency will create large cavitation bubbles, whereas a high frequency makes smaller cavitation bubbles – the ideal rate depends on what you’re cleaning. For the most part, engine builders find low frequencies to work well with engine components such as cylinder heads and blocks, but small pieces may be cleaned at higher frequencies.

According to Logan, most parts washers have set frequency transducers. “40 kHz is a good compromise sound frequency giving good soil cleaning with minimal substrate damage. Steel substrates are impervious to damage during the cleaning cycles at 40 kHz.”

While frequency is essential for cleaning greasy parts, so too is the sweep rate. “A fixed rate frequency sends a fixed signal through the water and may allow for a higher possibility for part damage because of hot spots created in the same area during the cleaning process,” says Rich Panebianco, global OEM sales manager for the CTG Group, manufacturers of Blackstone-NEY Ultrasonic. “Whereas sweep is the constant moving action of the ultrasonics within the tank thus preventing hot spots from being created.”

Besides the frequency, the chemicals used in ultrasonic cleaners are essential, too. According to ArmaKleen’s Logan, ultrasonics can be sufficient with just a water carrier for the sound waves, but if you are talking about greases, oils and other hydrophobic hydrocarbons, the ultrasonic waves will not be able to make those types of soils dissolve into the water. “Using cleaning chemistries with surfactants and other additives which enhance water’s ability to dissolve hydrocarbon soils allows those hydrocarbon soils to be removed by the ultrasonic waves from the substrate.”

If you are using a chemical stronger than water, the solution will need to be monitored and changed, depending on how dirty the parts are and how often the system is used. Logan asserts that the chemical solution is “dependent on the soil loading of the part, the size of the ultrasonic bath, and the number of parts being put through that bath.” In short, he says, “The bath should be changed when you see a drop off of the cleaning effectiveness.”

After changing the cleaner, foaming can sometimes be a problem for an ultrasonic machine after it is first turned on. “The cleaner bath will have dissolved atmospheric gases,” Logan continues. “The ultrasonic waves will de-gas the cleaner. During this initial de-gassing, you can create some foaming. It is recommended that the bath is heated to its operating temperature before this initial de-gassing. The higher the temperature of a cleaning solution the less gas will be dissolved. And if the cleaner is a multi-machine compatible cleaner, its defoaming agents will be activated by the elevated temperature.”

Our experts say that most of the time the parts can be left to clean by themselves in the ultrasonic washer, which allows the technician to move on to other tasks and become more productive in the process. “Initially the tech will come back to the part being cleaned periodically,” notes Mike Hansen, director of parts cleaning technologies at Safety-Kleen & ArmaKleen. “But as they become familiar with the ultrasonic cleaning process, they will get an idea of how much time it takes to clean most of the parts they encounter. Depending on the customer’s specific application, no additional cleaning is usually needed after the ultrasonic cleaner. In some cases, a quick final rinse or a wipe down of the part might be all that is required before moving on to the next step in the machining process.”

The use and acceptance of ultrasonic cleaners in engine building shops is on the rise for many reasons, but if the return is not there, then most shops wouldn’t purchase one. While the machines are more expensive than conventional cleaning systems, we wanted to know how long it would take for a shop to reach a break-even point on their purchase and what kind of financing is available.

ROI on ultrasonic cleaners depend on how many workers and hours are committed to a manual cleaning process compared to the manpower and time saved by using ultrasonics. Some ROIs are 4–6 months and others a year.

Panebianco says that ROI on the equipment depends mainly on how many workers and hours a company has to commit to their manual cleaning process compared to the manpower and time they will save by using ultrasonics to do their cleaning. “We have seen ROIs as quick as 4 – 6 months and in other cases 10 months to a year or longer. It just depends on understanding your current process, what you want to accomplish and determining a timeframe your business can live with for an ROI.”

Hansen says that most equipment companies will offer an independent financing/leasing company to help shops buy the equipment they need. “In most cases that I have seen the customer will finance/lease it 24 to 36 months with a $1 buyout at the end.”

Many smaller shops will start with a small tabletop to see the saving results in the beginning,” Panebianco adds, “only to come back for a larger unit once they have seen the overall benefit and money savings.”

If you want to reduce your cleaning time and still maintain your quality standards, now may be a good time to look toward the future and add an ultrasonic system into the mix. The sound of cleaning may not reach the level of Julie Andrews, but the money you’ll save in the long run will undoubtedly give you a boost.