Motorcycle Drag Race Engines

Back when we started to get serious about competing in the V-Twin drag racing scene, there were four or five manufactures making engine cases, heads, crank/flywheel assemblies, and connecting rods, along with other parts for large cubic inch competition V-twin engines. At the time, the largest factory engines from Harley-Davidson were 80 cubic inch big twins and 74 cubic inch sportsters, both having the capability to be enlarged to 114 cubic inches with longer (more deck height), larger bore cylinders and longer stroke flywheels as the norm.

Related Articles

During this era in the ‘70s through the early ‘90s, aftermarket components began to emerge to replace the stock castings with stronger more versatile pieces eventually allowing engines of 140 inches and larger to become commonplace. This was also a time when Top Fuel and its siblings used very similar, and sometimes even the same, basic engines as their gas burning cousins.

As the nitro burners began to overpower the old knife and fork connecting rod designed engines, racers and builders, in particular Jim McClure, began to solve the problem by designing a billet side-by-side rod engine suitable for the application of nitro racing. Using connecting rods much like the Top Fuel Hemi example, along with an entire engine built around it, Jim and his team raised the bar in V-twin Top Fuel racing like the Top Fuel dragster/Funnycar contingent had done in the early ‘70s.

Later, others such as Johnny Vickers with his Derringer program and PRP setting the standard in Pro Fuel and Top Fuel would come along. Manufacturing cylinder heads for these programs predominately was and still is Don Losito’s Ultra-Pro Machining.

The reason I touch on the evolution of nitro engines is because this is a great example of new, purpose-built components coming to a small niche market, thus enabling a sport to grow in numbers both in performance and participation. The birth of CNC machining and its availability to small shops and manufacturers allowed this to happen, and also fueled a renaissance in manufacturing to great effect empowering domestic machining to compete in a world market.

The gas racing cousins I mentioned earlier were also producing more application-specific engine components. This was a much larger market because of gas racing components and engines also being used by the street and custom market, or vice versa. With such a huge difference in demand, investment in engineering programs and tooling used by foundries for casting parts in quantity was much more suitable than individual billet parts. However, this started to die off after the custom bike craze of the 2000s was gone. The custom trend I mentioned grew so fast and so large that many aftermarket manufactures grew with it and were not prepared for the rapid decline in demand when the party was over.

Harley-Davidson factory engines from 2000 to present day are capable of being much larger than those prior to 2000. Today, a competition version of their latest V-twin at 131 cubic inches and aftermarket parts available to allow 150 inches in factory cases, has satisfied much of the modern demand for gas racing or performance customers.

A rapid decline in demand along with the mother ship of the market feeding its own aftermarket, left most companies previously supplying V-twin racing components “out of business.” This is why we decided to follow our nitro racing friends into producing our own racing parts in billet.

We had great success using the S&S cast “Pro Stock” and “Street Pro” engines and components as a foundation for our in-house engine program. As power and engine speeds increased, we modified the available parts to suit our needs, ending up with something that resembled the original part only from the outside. We are not the only ones who followed this path, just like in the automotive world, motorcycle racers will be the source of much innovation relevant to their situation and requirements. There were many others before, who like us, decided to make their own parts, mostly due to having a better idea to suit their own needs.

Our biggest problem was that S&S had ended production of the parts we depended on to keep our engines flowing. S&S is the largest contributor to our aftermarket and we understand that they are simply responding to declining demand and refocusing on better segments as it relates to their overall plan.

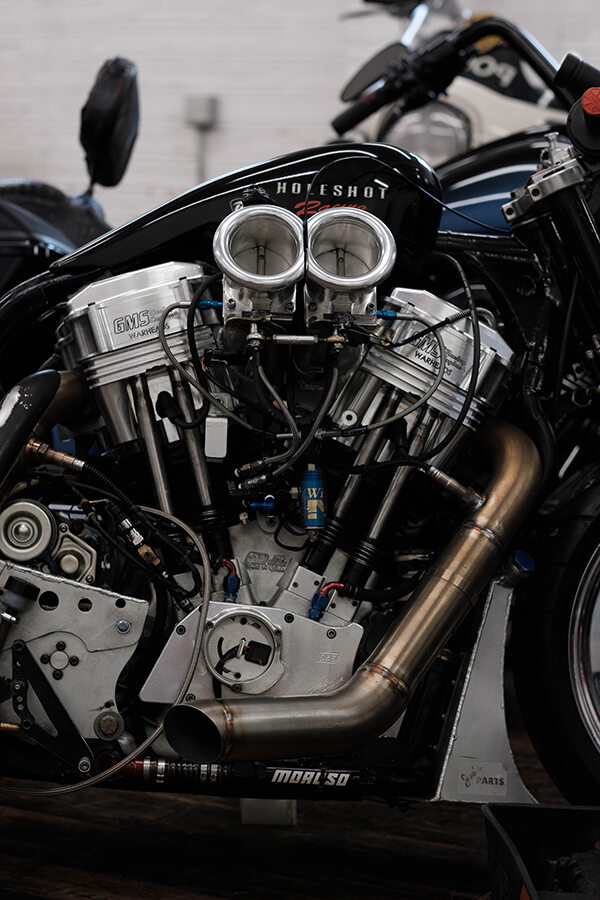

With all of this coming down on us, we were still faced with a growing niche that we had to fill in order to stay in business and to continue to race and develop new things like our in-house fuel injection program spearheaded by GMS engineer Damon Kuskie.

Not having a CNC shop onsite didn’t slow us down. We knew we could use capabilities that CNC manufacturers had locally. Not long before we started to get serious about proprietary engines, I found a shop that could scan our models and produce our parts. The process took about two years and was expensive, but we were able to sell enough components to cover most of the cost on the first run.

Not only were we able to incorporate all of our modifications into the new program, but we also were able to do things not possible with the parts we had before.

R&R Cycle in Manchester, NH had been making strong, attractive crankcases along with other parts from billet for years and were one of the few companies that survived the market shift. They had a dual-cam V-twin engine that could go to 4.600˝ bore and had built engines to 155 cubic inches with that case. When Randy Torgeson of Hyperformance in Pleasant Hill, IA suggested I go see Reggie Ronzello at R&R to talk about a new engine case, I did exactly that. We sat down at Reggie’s in-shop espresso bar to discuss what I wanted to do – 5.00˝ bore, relocate the sump in the flywheel cavity, removable bottom plate, room for our giant aluminum connecting rods, option for charging system delete, timing notches for crank sensor (R&R now makes our flywheels used in our crankshaft assemblies as well), and using the bolt patterns that our previous combinations had for cross application of parts. Since then, I have added an adjustable oil feed to the cam plate that will be included in future cases.

Moving to the cylinders, I simply called Randy at Hyperformance to handle that part of the package. They are either 4.800˝ or 5.00˝ bore in various lengths made from 90,000 PSI ductile iron. This material is well suited to this application and hones nicely.

S&S had been making a really good connecting rod for some time – it was a 7075 alloy billet rod in lengths of 8˝, 8.250˝, and 8.500˝. When production ended for that part, I began to have our own made with some changes to fit our new program. We came up with a little different surface finish, adjusted the press fit slightly, added a cryo and tempering process, and modified the installation of the bearing races into the rod. We are also currently designing a rod to use a much larger crankpin to stiffen the crank assembly and allow room for a better rod roller bearing.

The billet cylinder heads were a combination of several different ideas coming together in what you see here and have appeared in my other articles. I had a couple of S&S semi-finished castings that had been laying around for years, so I decided to start with them. I remember seeing a photo and reading about Wally Booth’s AMC heads where he and Dick Maskin took the existing AMC heads and cut mutable sets up, reassembling them to get a high port, then having them cast at the factory. Something like this would be much easier with aluminum motorcycle heads, so I decided to try it just to make a model. I raised and reshaped things until I had what I wanted for a model. I sat on this for quite some time until I could finish the project.

Jesel Valvetrain had an excellent rocker arm retrofit for the S&S cast Pro Stock head that required the top 5/8˝ of the head machined down to make room for a steel plate and the relocated rocker assembly with covers. Starting from scratch, I incorporated the mounting bosses into the billet head so Jesel’s super strong rocker arms would fasten directly to the head. I took my models to Chaos Fabrication for scanning and began receiving parts soon after.

I cannot over stress how important it is to have good relationships with the venders and companies that are in this industry. Everyone I mention in this piece has been excellent to work with and delivered what we needed when we needed it. We now offer these engines ranging in size from 144˝ to 172˝ with 8,500-9,000 rpm capability.

Like the Top Fuel racers mentioned above, we have taken advantage of the CNC revolution using both industry and local resources to achieve our goal of having a proprietary racing engine that will help keep our little corner of the racing world alive. Since we had the opportunity and the need, we decided to risk the investment and make it happen. We’re glad we did.

All photos were taken by Kimberly Wyatt of Kimberly Marie Photography